Convened the Greater Gulf Symposium, April 15-16, 2024

|

The highlight of my academic year is convening the Third Annual Greater Gulf Symposium as director of the Center for History and Culture and Lamar University. This year, we coordinated with Symposium Chair Tara Dudley (UT Austin) and invited six Symposium Fellows--Timothy Grieve-Carlson (Westminster College. PA), Asma Mehan (Texas Tech), Andrea Ringer (Tennessee State), Kelley Robinson (Florida State), Barry Stiefel (College of Charleston), and Jermaine Thibodeaux (University of Oklahoma)--to workshop their projects on the built and unbuilt culture of the greater Gulf region. As in past symposiums, we enjoyed a warm spirit collegiality and camaraderie. I felt privileged to spend these several days with intelligent and curious people who ask interesting questions about important subjects and who enthusiastically support each other's work.

|

Presented at the Society for the Study of the American Gothic, March 22, 2024

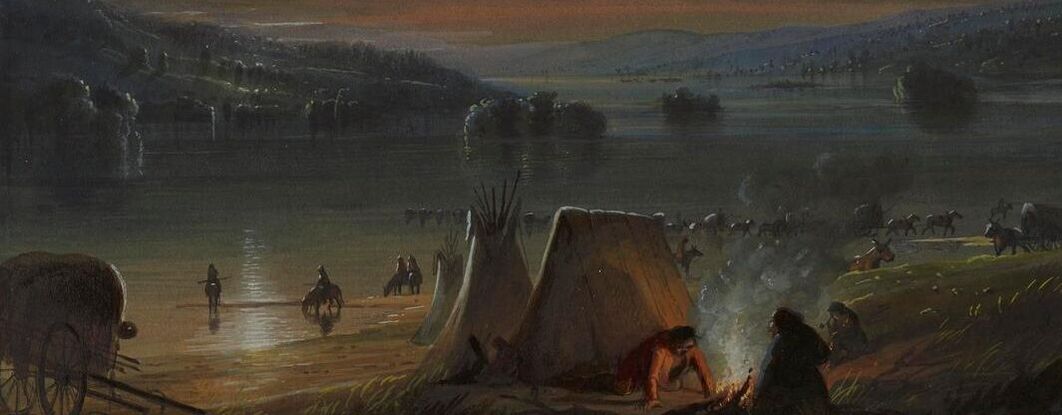

I presented at the inaugural symposium of the Society for the Study of the American Gothic at Salem, Massachusetts. My paper entitled "I Tore Out All Their Hearts: Maniac Fathers on the Expansionist Frontier" is part of my larger book project This Empire Grim (for more information click here). In the frontier literature of the early nineteenth-century, the Indian Hater figures as a kind of antihero whose vengeance for the loss of family members justifies the violence against Native Americans and thereby sanctions the territorial expansion of the United States. But viewed as a gothic madman, the Indian Hater becomes a dark warning to those fathers who follow their avarice into contested borderlands and sacrifice their wives and children on the altar of manifest destiny. Driven insane by their severe shame for having failed their roles as protectors of their families, the maniac fathers found in the works of James Hall, Robert Montgomery Bird, Charles Wilkins Webber, and others are tragic characters whose violence appalls and demands condemnation.