Artwork of The American Elsewhere

Click on the images for larger full-color versions and for more information. All Alfred Jacob Miller works link to the Fur Traders and Rendezvous website. All images under Fair Use.

|

Fig. 1.1. This image originally appeared in George Wilkins Kendall, Narrative of the Texan-Santa Fe Expedition (1844). The vast buffalo herds became emblematic of American elsewhere, and the chase became a ubiquitous feature of the adventurelogue. Jordan and Halpin after J. G. Chapman, A Scamper among the Buffalo (ca. 1844). Courtesy of the Beinecke Library, Yale University. Links to Wikimedia Commons.

|

|

Fig. 1.3. This image originally appeared in James O. Pattie, The Personal Narrative of James O. Pattie of Kentucky (1837), edited by Timothy Flint. Hardships like thirst and starvation added to the perils that instigated emotional experiences that adventurers anticipated would lead to personal transformation. William Woodruff, engraver. Messrs. Pattie and Slover Rescued from Famish (c. 1837). Courtesy of the Beinecke Library, Yale University.

|

|

Fig. 2.1. In the early 1820s, improving print technology enabled Samuel Seymour to produced one of the earliest published, first-hand visual depictions of the Rocky Mountains. Francis Kerney after Samuel Seymour, View of the Rocky Mountains on the Platte 50 miles from their Base (c. 1822). Engraving. Courtesy of the Library of Congress.

|

|

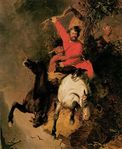

Fig. 2.2. Charles Deas excelled at painting narrative scenes infused with the violence inherent in adventure, capturing emotional intensities like defiance and terror. The Death Struggle (1845). Oil on canvas. Original painting at the Shelburne Museum. The version reprinted in The American Elsewhere is an engraving by William G. Jackman (c. 1846). Courtesy of the Art and Picture Collection, The New York Public Library. Links to Wikimedia Commons.

|

|

Fig. 2.3. In 1831, Washington Irving was already one of the most read US authors, and a year later, he embarked on his prairie tour. Moseley Isaac Danforth after Charles R. Leslie, Washington Irving, Esqre (1831). Stipple engraving and etching on chine collé on off-white paper. Courtesy of the Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts, Philadelphia.

|

|

Fig. 3.1. The material culture of the backwoodsman—the fringed buffalo-skin jacket, fur cap, buckskin moccasins, and long rifle—attested to the exceptionalism of the American male. Abel Bowen, frontispiece for Estwick Evans’s A Pedestrious Tour (1819). Woodcut. Courtesy of the Beinecke Library, Yale University.

|

|

Fig. 3.4. The figure of an Indian standing proud and indomitable against the forces that threatened his ruin struck at the essence of romantic melancholy. Alfred Jacob Miller, Crossing to the North Fork of the Platte River (1858-1860). Wash heightened with white on paper. Courtesy of the Walters Art Museum, Baltimore.

|

|

Fig. 3.6. Charles Deas displayed Long Jakes at the American Art-Union in New York City, and it attracted crowds of urban dwellers who recognized the embodiment of peerless masculinity. Deas, Long Jakes, the Rocky Mountain Man (1844). Oil paint on canvas. Courtesy of the Denver Art Museum. For more information see post on Elsewheres blog.

|

|

Fig. 4.3. Public bathing and scant attire of Indian and Mexican women fueled the popular fantasy of young, beautiful, and naked girls awaiting Anglo-American men. Alfred Jacob Miller, Indian Girls, Swinging (1858-1860). Watercolor heightened with white on paper. Courtesy of the Walters Art Museum, Baltimore.

|

|

Fig. 5.1. The expedition functioned as a community of adventurers and provided the stage for their masculine performances. Archibald Dick after Eugene Didier, Arrival of the Caravan at Santa Fe (ca. 1844). Engraving. Courtesy of the Beinecke Rare Book and Manuscript Library, Yale University. Links to New Mexico Digital Collections.

|

|

Fig. 5.3. The Mier Expedition—formed by men who refused to follow orders and disband—illustrated the crisis of leadership evident in many adventurous organizations where every man was his own captain. Hillyard and Prudhomme after Charles McLoughlin, Mier Expedition Descending the Rio Grande (ca. 1845). Courtesy of the Archives Division, Texas State Library, Austin.

|

|

Fig. 6.1. In the 1830s, peoples of different ethnicities and nationalities converged upon this trading post at the junction of the Laramie and North Platte rivers deep within the American elsewhere. Alfred Jacob Miller, Interior of Fort Laramie (1858-1860). Watercolor, heightened with white, on paper. Courtesy of the Walters Art Museum, Baltimore.

|

|

Fig. E.1. With the nation spiraling deeper into the sectional crisis between the North and the South, John C. Frémont’s 1856 run for president, in part, reopened the challenges to the western adventurer as American hero. Baker & Godwin, Col. Fremont planting the American standard on the Rocky Mountains (1856). Wood engraving with letterpress. Courtesy of the Library of Congress.

|